Now where was I … oh yes. Frankenstein and Promethean fire. And the promise of ghosts and spiritualism. But first, something happened that we need to talk about.

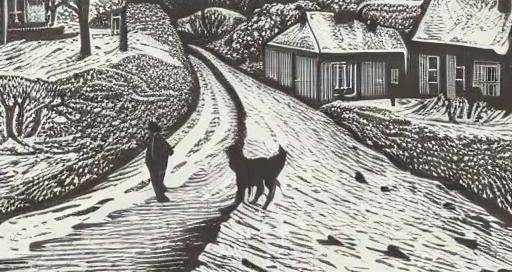

In the deep midwinter ...

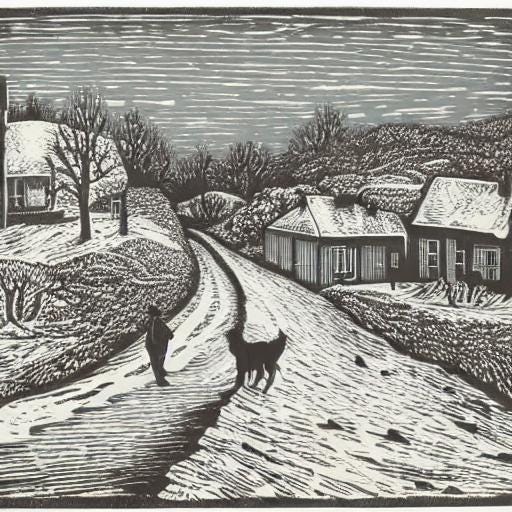

It’s a cold, midwinters morning and I’m walking the dogs on the borders of the Woiwurrung, Taungurung and Dja Dja Wurring peoples. It’s cold and crisp, but the frogs are still singing happily. They don’t mind the cold and wet – this is a swamp after all.

Frost glistens before me and betrays my path behind me. It’s crazy cold: “Feels like minus 2” says the weather app.

As I walk, I’m listening to Mythos, Stephen Fry’s retelling of creation stories courtesy of the Greek Myths. His mellifluous voice is telling the tale of Zeus’ attempted revenge on Prometheus courtesy of Pandora - a woman of course, but don’t get me started.

The tale goes something like this:

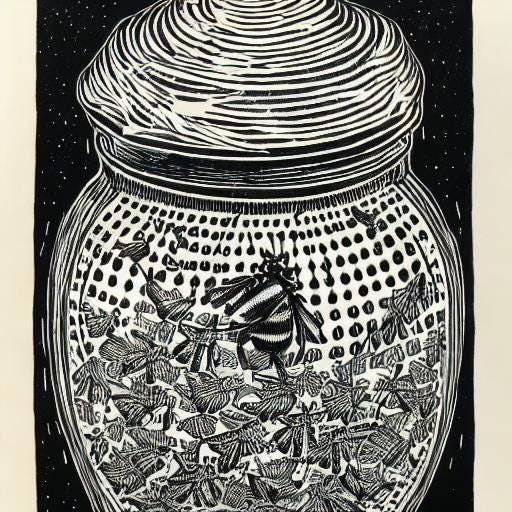

Zeus, simmering away at Prometheus’s betrayal (he stole divine fire and then gave it to humans), creates the first woman, Pandora. He sends her as a bride offering to Prometheus and with her, a wedding present – a box (or rather, a jar or an amphora) which is not to be opened until after the wedding.

Pandora is, of course, gorgeous. She is vibrant and funny, smart too, though not immune to Zeus’ evil plan ... Prometheus is quite sensibly, suspicious. Zeus was his best friend after all, and he knows him well. But Prometheus’ brother Epimetheus, falls for Pandora ‘big time’ as my daughter might say, and plans the wedding.

On the night of the wedding, Epimetheus has to pop into the office – something to do with fire and humans reaching their potential. Meanwhile, Pandora, bored and possibly nudged by some Zeus trickery, decides to open the wedding present. And well, you know the rest …

Released into the world are all the evils that have beset humankind ever since. These are the children of the daughter of Nyx, they are disease, malice, hunger and war, that kind of thing. They exit the amphora like locusts, buzzing maliciously out and into the world, wreaking havoc forever more.

It’s an old story, arguably a cliché wrapped in a chestnut, but bear with me …

As I walked, mist rising from the path ahead, I found myself particularly relishing Fry’s reading of each of the released Greek evils.

PONOS, Hardship; LIMOS, Starvation; ALGOS, Pain; DYSNOMIA, Anarchy; PSEUDEA, Lies; NEIKEA, Quarrels; AMPHILOGIAI, Disputes; MAKHAI, Wars; HYSMINAI, Battles; ANDROKTASIAI and PHONOI, Manslaughters and Murders.” (Fry, 2018, p.137)

Unintentionally, I begin to keep time with his rendering, each footfall echoing a name.

It’s almost mesmeric hearing the names of the evils spoken aloud; each name marking a rhythm of dread and sadness, the insistent patter of eternal strife rendering an endless and anguished beat.

Even the dogs look a little downcast.

Later that morning as I drive to work, I listen to Kate Crawford’s Atlas of AI - an incredible book that delves into the material and political forces shaping AI and the world around us.

The environmental impact of AI and broader digital technologies is truly alarming. The mantra "3 buckets of water" echoes in my mind with each AI prompt, reminding me to use AI judiciously and remain aware of its significant power demands.

Crawford's work largely informs this internal voice, making it essential reading for those assessing AI's implications in education.

As I navigate roadworks, Crawford outlines the extractive nature of AI and of digital technologies more broadly. She argues that the industry deliberately uses phrases like The Cloud and Artificial Intelligence – as light on the earth as a breeze or consciousness – to belie the weight of their planetary impact.

“AI can seem like a spectral force—as disembodied computation—but these systems are anything but abstract. They are physical infrastructures that are reshaping the Earth, while simultaneously shifting how the world is seen and understood.” (Crawford, Kate, 2021, p. 19)

Crawford takes us to the places and spaces that push back against such marketing. We are invited to wade through the toxic and reeking black lakes that are the result of waste run off from the Bayan Obo mines – a mine containing roughly 70% of the world’s rare earth minerals. We journey through lithium mines and into the circle of hell that is Amazon’s shopping warehouses.

As we follow her, a disturbing social and planetary image surfaces, in which systems of power and money dominate the production of digital technologies, including AI – the latter of which she argues carries the lion’s share of harm.

“…artificial intelligence is both embodied and material, made from natural resources, fuel, human labor, infrastructures, logistics, histories, and classifications. … And due to the capital required to build AI at scale and the ways of seeing that it optimizes AI systems are ultimately designed to serve existing dominant interests.” (Crawford, 2021, p.33)

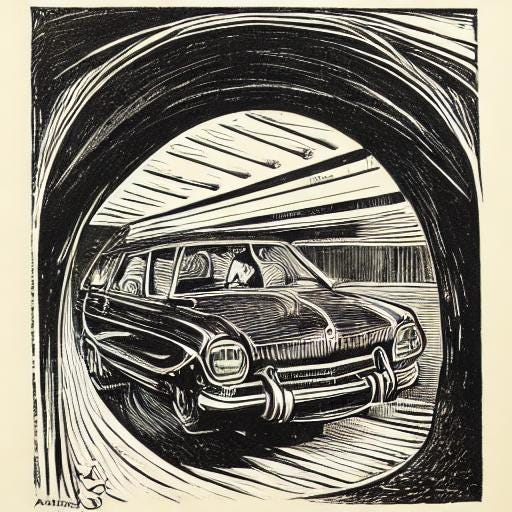

Sitting deep below Melbourne in the Burnley Tunnel, surrounded by traffic and darkness, I follow Crawford as she discusses the critical role of the mining industry in the production of digital technologies.

To counter the myth of clean tech, she applies a forensic lens to the materiality of the digital industry. In this chapter, she is focusing on the social and planetary costs of mining, detailing the consequences of extracting precious minerals from the earth.

There are seventeen rare earth elements, Crawford tell us, and in 2020 dysprosium, neodymium, cobalt, dysprosium and neodymium, were all listed as a supply risk. All these elements are used variously in mobile phones, laptops, electric vehicles, and a stunningly extensive range of digital products – including AI. Without them, Crawford tells us, the industry would collapse.

Aware that my chest is tightening as I process this information, I hear something familiar. Crawford is reading out the list of rare elements. Her rendering is rhythmical, musical almost meditative:

…lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, neodymium, promethium, samarium,

europium, gadolinium, terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium, thulium, ytterbium, lutetium, scandium, yttrium. (Crawford, Kate, 2021. p. 33)

That patter, that rhythm, so deeply familiar … they could almost be the long-forgotten names of the offspring of the daughter of Nyx.

Deep under Melbourne, in the dark of the Burnley tunnel, I think about the meaning of all this. Do I see this juxtaposition as a metaphor for new evils? Do I interpret this as a measure of ineffability - the unseen and the seen? Is it just another case of pattern seeking?

And then I think I get it: I’m hankering for hope.

When Pandora in her panic slapped back the lid on the vessel from which all the evils in the world had spilled, she imprisoned one last wasp. Elpis, or Hope. Daughter of Nyx, who we are told remained a prisoner, left alone “…to beat its wings hopelessly in the jar for ever” (Fry, 2018, p.137).

Now there’s been a hell of a lot of ink spilled on the significance of this last wasp, so let’s not get too bogged down. But in brief, here are three ways we might consider the significance of hope:

Hope as solace: Even amidst the multitude of evils, humanity retains hope as its steadfast companion.

Hope as deception: Hope serves as a bitter deception, ensnaring the very thing that could have aided humanity in confronting the unleashed horrors.

Hope as possibility: Its confinement in the jar symbolises the ever-present potential for a brighter tomorrow, perpetually elusive yet eternally present.

A car behind me honks, I’m sitting at the wheel deep in thought while the traffic around me surges on. But I think I know now how to make sense of this difficult experience. How to make some peace with the work and the world.

And it’s all about systems. Broken ones.

For over18 months I have been absorbed in the world of AI and its implications for teaching and learning in higher education. Like many others, I have traversed the highs and lows of this changing and complex landscape with both excitement and existential dread.

For whilst I am hopeful that AI will cure cancer and dementia, and while I dream that these technologies may very well help us to redress climate change, my context is education. And I’m yet to see a beacon of hope shining from these ivory towers.

And there’s a good reason for this. It’s because AI has been sold to us as above all, a way to improve productivity. It’s the solution to overwork, to poor student engagement, to the administrative nightmare of quality assurance, to the challenge of teaching to large classes and marking many hundreds of essays in record time.

But this isn’t the problem - the problem is the outdated systems of learning we remain wedded to.

In brief: We over assess, we offer little scope for actionable feedback, we prioritise artefacts of learning over processes of learning, and we do this at scale with big classes and with diminishing opportunities for relationship building. And it’s not just me - the literature is awash with critique and challenge to current practice. (Bearman et al., 2016; Boud, 2020; Boud & Falchikov, 2007; Havnes & Prøitz, 2016; Tai, 2023)

Added to this are the challenges for students in the current context - crises in cost of living, in housing and the escalating issue of mental health post 2020. For those of us in universities with cohorts drawn from a broader cross-section of society, the impact of these factors can’t be underestimated. Attendance and participation are negatively affected. The risk of students resorting to cheating is intensified. Life is hard for our students at the moment, and it may very well get harder.

When AI is added to the picture, with the attendant risk to assurance of learning, we have a point of departure not often offered. We have an opportunity to change the way we do things in higher education. To think about what learning means for our students. To reassess how we support students through learning in the humanities - in the creative arts, in the social sciences and in those contexts wherein concepts, ideas, creative works and original thought are anything but transactional.

This is what I found in the Burnley tunnel. Hope.

Whether it remains stuck in its jar is yet to be seen.

Find out next time, as I draw on Ada Lovelace and the spiritualists for help.

I want to go on a road trip with you Fran. If a drive through the Burnley Tunnel results in those thoughts and words, you're my new driving buddy.

You write so beautifully and provide us with so many insights on this wild new AI world.

Beautifully written and I love how this ended up in education. I wholeheartedly agree!